I just read an interview in the NYT with marine biologist Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson. (The interview might be behind a paywall—sorry.) In it, she says, “Sixty-two percent of adults in the U.S. say they feel a personal sense of responsibility to help reduce global warming, but 51 percent say they don’t know where to start.” I was in both of those groups, but now I’m only in the first one. For better or worse, I’ve decided where to start and I’ve been on that path for a few years. Relating my experiences may help some of you Gentle Readers to get started, or to guide you. I hope so.

I’m not an authority on this complex subject, but Bridget and I have always been thoughtful about the resources we use. Trying to reduce our carbon footprint became part of our larger effort to tread lightly on the Earth, so as not to spoil the place for future generations. We try not to throw away greenhouse gases (GHG) in the same way that we try not to throw away trash on the hiking trail. Trash is easy, gases are not. In this post I record honestly how we’ve approached that problem, despite my sad sense that we could surely have done better if we had known more. I hope we haven’t made the problem worse. The fundamental question is, how can we all take advantage of modern opportunities for a better life while moving away from trashing our planet? That’s what this post is really about and the truth is that the answers aren’t clear yet. But I think that doing nothing is morally wrong. I hope that your path will be better than mine.

Foundation and motivation

Let’s start with the basics. Bridget and I both have decades of personal experience where trusting scientists has worked out very well for us. Bridget is a pediatrician and by trusting scientists, she has saved many children from death. These aren’t statistics; she can name them. I’m part of a scientific community and every scientist I’ve known has shared my deep desire to help people by making genuine true predictions, not by making up stuff we like. We scientists made better predictions by respecting one another and working together, including relentlessly critiquing one another’s ideas and accepting those criticisms. So Bridget and I have concluded by our experience that scientists are imperfect, but worthy of our confidence. And when almost all of the climate scientists agree that human production of greenhouse gases is going to make our planet hard for us to inhabit, and that our choices now can make that disaster better or worse, we believe that this is not a conspiracy nor a political view, but a thoroughly scrutinized technical prediction from many skilled people who are perfectly eager to disagree if the evidence allows them to. It doesn’t.

We are also amateur geologists and we know that the earth has been very different many times in the past and if a climate change happened fast enough, most living things on the planet died from it, and most species died out. Mass extinctions from climate change have happened many times; they are right there to see in the fossil record, defining most of the geological periods. So a mass extinction can happen again. It could include humans. In at least one past case, living things poisoned the entire atmosphere (with oxygen!), changing the whole chemistry of the earth’s surface. Yes, it’s possible for a species to wreck the whole planet. It’s been done. We may do it again. The geological viewpoint tells us that our actions now will affect dozens, perhaps hundreds, or even thousands of generations of our descendants. Their world is in our hands.

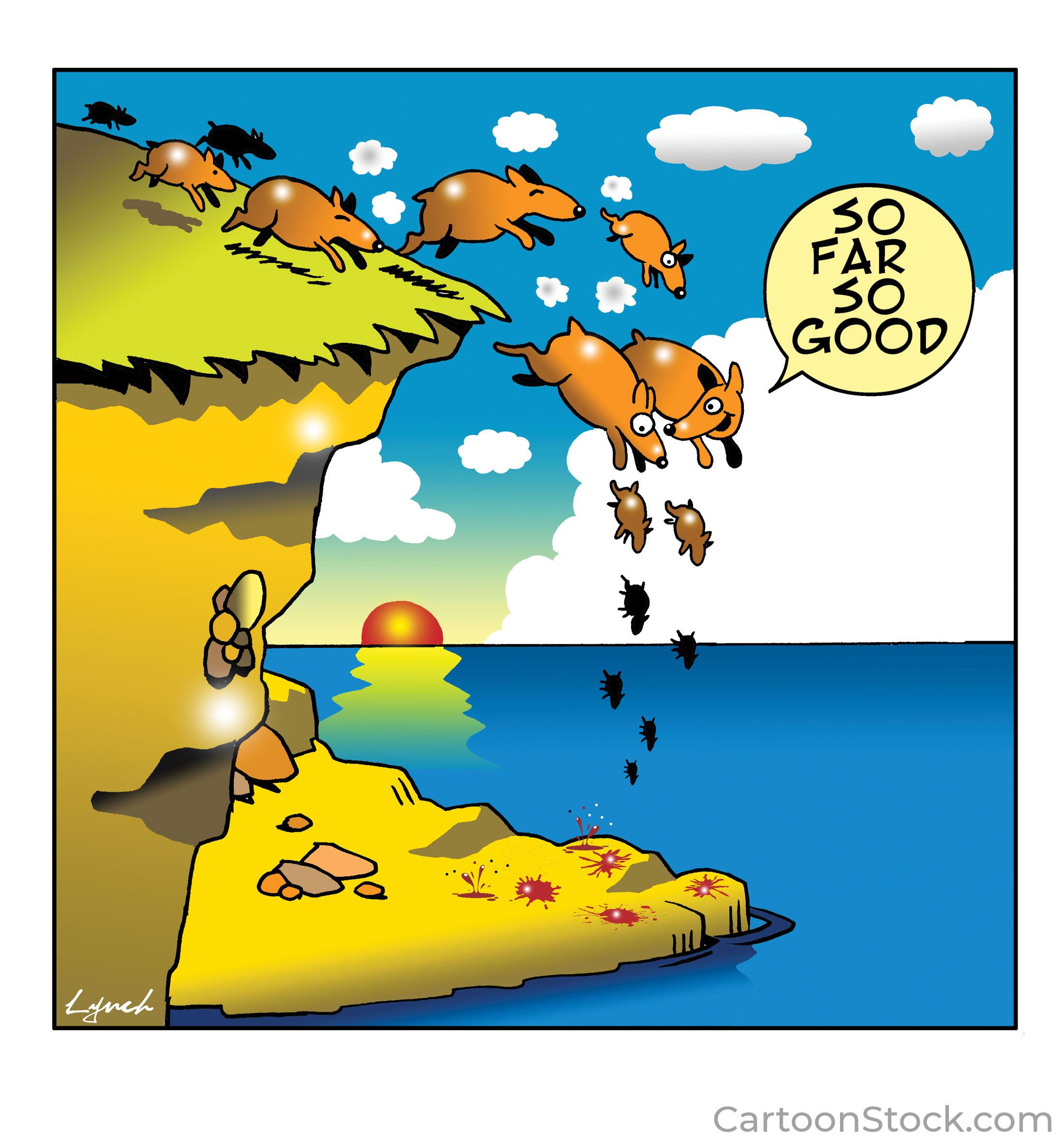

The greenhouse heating effect is very simple physics and the easily measured 50% increase in atmospheric CO2 in the last century works out to just about the amount of fossil fuel we’ve burned. There is no other new source. We did it—we actually heated our planet. This is not about accepting or denying a feeling of guilt; it’s just inescapable truth. Scientists are also well equipped to predict where this massive impulse will lead, depending on the choices we make now. The only reason we’re not mostly dead already is that our huge planet responds over centuries to any sudden damage input short of an asteroid strike. But we’ve set this damage in motion and it’s inevitably going to get very hot and nasty for centuries, or a millennium, or longer. Lots of species will die out, just like many others did in the past. It astonishes me that we are just coasting along as if we weren’t heading for a cliff that will kill millions of us.

Probably our species won’t go extinct, because we are so adaptable. Some of us will save a lot of us, but many of us will die anyway. Well then, we’d better start adapting right away. Or else we may be among the body count. The internet is full of hyperbole, but I think this is just facing up to reality.

Paper or plastic?

So I’m trying to react effectively to this oncoming disaster. I thought, “I have two approaches: I can try to change what others do and/or I can try to change what I do.” Trying to change what others do is called politics and I live in a state where the elected officials are already well aligned with my views on this subject. In Massachusetts, it’s much easier to change what I do than to improve what others are already doing. But it’s not so easy to figure out what to do. Every choice we make has a carbon impact and studies conflict over which alternatives are better. That landscape of trade-offs keeps changing and it encourages paralysis. But one thing is clear to me: if we stay on our current path, we really will “cook ourselves”. Change, even with all of its uncertainties, seems like the better option to me. I guess that sounds desperate and … it is.

In principle, I’d like to stop producing greenhouse gases altogether, but I’m not willing to give up exhaling CO2 or farting methane. (Well, I’d be happy to give up the methane part, but never mind.) And I’m not willing to live in a cave and eat local roots and tubers in some weird form of penance. However, I figured that Bridget and I could gradually “just say ‘no’ to fossil fuels“. What I mean by “gradually” is that, when it’s time to replace a device that burns fossil fuel, could we choose a replacement that does not burn fossil fuel? In a lot of cases the answer is yes. But any new component has already put greenhouse gases into the atmosphere just by being made. It’s called “embodied carbon”, which is a bit of a misnomer, because that carbon is loose in the atmosphere. But in the absence of specific studies, I just assume that the carbon emission to make one type of replacement component is equal to the emission to make any other type. That’s probably not true, but without very careful studies, one has no reason to favor one type of component over another. So, after checking for such studies, we have so far picked non-fossil-fuel replacements. Here are some examples.

Just say no to coal?

This turns out to be pretty easy in many places, including Massachusetts. According to the US Department of Energy, “At least 50% of customers have the option to purchase renewable electricity directly from their power supplier”. Check it out where you live. In Massachusetts, we switched to a 100% renewable electricity plan years ago. Many towns and organizations sponsor and negotiate group plans for their residents or members. Ours comes from the town of Sudbury and we signed up on the town website. Initially, it was costing us more than the standard plan, but now it is comparable.

You know, at first this seemed like some sort of weird accounting fiction to make us feel good about “being green”. I mean, those electrons we buy aren’t labeled and sorted, so we can’t weed out the ones produced by say, a coal-fired power plant. But here is how this works. When we buy our kilowatt-hours monthly from a renewable source, they get paid to produce the amount of power we used, and the coal plant stops getting paid for the power we used. We literally shut off our personal demand for fossil fuel-based electricity and give that demand to somebody who operates a windmill, solar farm, or hydroelectric dam to help them get a return on their investment. Let’s make a deal.

But we don’t get to make that deal in Gainesville, Florida where we’re building a winter home. The city of Gainesville has its own utility that makes some of its own electricity (some from coal!) and it buys the rest regionally. Customers do not have a choice of sources. But in “The Sunshine State”, couldn’t we make our own solar electricity? Seems like a no-brainer. Well, our particular lot is covered in big old trees that soak up lots of CO2, but the shade would make solar panels a flagrant waste of resources. Best to let the trees keep doing their carbon capture thing. And the shade cools the house, reducing our energy needs. So in Gainesville, we can’t shut off our demand for fossil fuel-based electricity … yet. When we move there, I plan to engage with the utility on this issue and ask for a renewable alternative plan.

Right now one thing we could do in Gainesville is to encourage renewable electricity production in general by buying retail Renewable Energy Certificates. This is an EPA-vetted channel that directly subsidizes renewable energy production, making it more affordable for “everybody”, but not more available to me. Basically, this is a charity contribution, not a utility payment. It does not reduce my demand for “dirty” electricity. Also, RECs may not be valid contributions to emission reduction. Despite good intentions and best efforts, they may be “greenwashing“. Hence my interest in convincing the utility to offer a direct renewable power option.

Just say ‘no’ to gasoline?

We’re getting close on this front. In 2019, I sold my 2008 BMW convertible and bought a Tesla Model 3. Man, I could never go back to an internal combustion engine. Not because I’m so “green” but because EV’s are way more rewarding to drive. With my foot on one pedal and my hands on the wheel, my car will instantly do anything I ask. Every internal combustion car I’ve ever driven was trying to be like this and failing. And, no noise. No muss, no fuss, no drama, no quirks; it just does exactly what I want. One time, Bridget and I were on a long straight uphill two lane road with a slow truck in front of us. Bridget gets nervous when I pass in situations like that. In the Tesla, I signaled, pulled left, depressed the accelerator, a giant invisible hand silently shoved us past the truck, and we were back in our lane like nothing had happened. O.M.G. I could never go back.

We’ve done road trips in the Tesla (I might post about that), but chargers are currently too sparse in some places to make this comfortable, so when it came time in 2023 for Bridget to replace her 2016 Subaru Forester (we put a lot of trip miles on that car), she bought a plug-in hybrid Toyota RAV-4. It charges at home alongside my Tesla, so she buys gas about every three months unless we’re on a trip. Her electric range is about 45 miles, so that’s good for most days.

Because we’re buying 100% renewable electricity, both of our cars account for no CO2 emissions most of the time. Their primary ongoing pollution is probably tire wear. I like driving my Tesla so much that I actually go on rides for several hours, just to go out and have fun cruising around. I figured that driving this car costs me $5/hour in renewable electricity, so the price of a joy ride is like going to the cinema. With no CO2 emissions, it’s good clean fun. Parenthetically, I can’t understand why Elon Musk wants me to pay him so that the car will drive itself. Yo, Elon, I bought this car because I like driving it more than all other cars. I tried a 30 day free trial of “Full Self Driving” and my reaction was, “gimme the wheel, you fool”. For me, “self-driving” was an awkward stunt by a clueless machine. And I dislike Musk’s behavior toward other human beings. When the time comes, I’m hoping my next car will be an electric BMW.We’ve gradually trimmed away our other dependencies on gasoline. I ditched my 20+ year old gas lawnmower for an EGO electric mower, also buying their leaf blower and chainsaw that use the same batteries. An electric chainsaw is a real treat. It’s fully off until you squeeze the trigger, then the torque is 100%, so the procedure is, 1) place blade on log, 2) squeeze trigger, 3) let go trigger when through the log. Repeat for over an hour. Swap batteries with one on the charger. There’s no smell and my neighbor can’t even hear it. Nice!

If you have a powerboat, that is a big source of carbon emissions. Water is heavy stuff and pushing it out of the way uses a lot of energy, even “on plane”. Most of the power produced by boat engines goes into generating the wake. In the coming years, hydrofoils may radically increase boat efficiency, basically by reducing the wake to almost nothing. I have an 18 foot sailboat, which I chose to outfit with an electric inboard motor instead of a diesel. It makes neither noise nor smell. (Joke: “diesel” = German for “filthy”.) It takes two hours to charge my batteries and then I have a 10 to 20 mile range, which covers the lake where my boat is based. When not under sail, I cruise majestically in eery silence. The folks at the marina call it my “Tesla sailboat”.

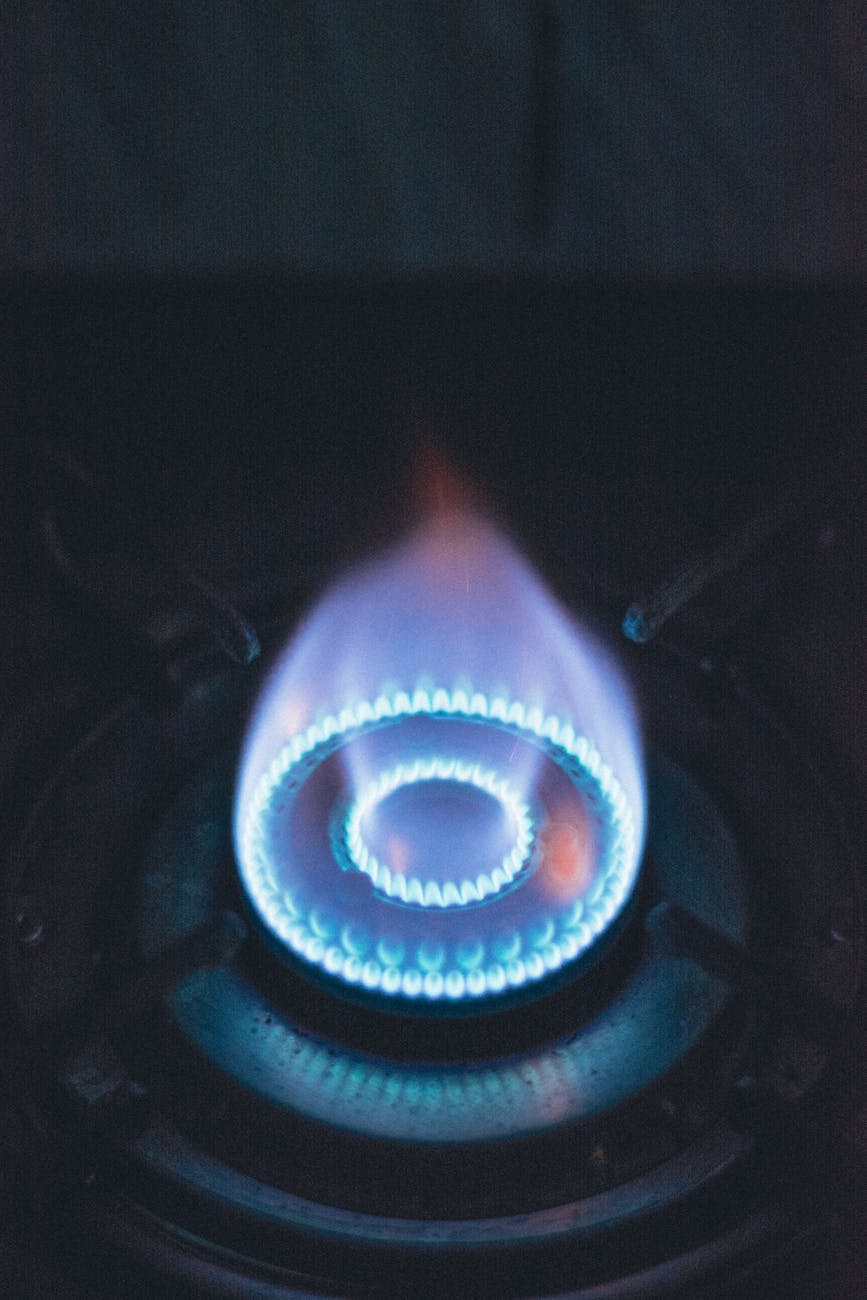

Just say ‘no’ to natural gas?

In Gainesville, we will not even pipe natural gas onto the property. No gas bill. HVAC, domestic hot water, and pool heat will all be from heat pumps. This will be much more efficient and reduce our carbon emissions, even though the utility doesn’t offer a 100% renewable electric supply (yet). We will also have a battery backup instead of a generator for the increasingly common power outages due to tornadoes and hurricanes. (Thanks, climate change.) In Massachusetts, our heat and domestic hot water come from natural gas systems that are only a few years old, so they are efficient units of their type, but they directly burn fossil fuel. If we are still the owners when those systems reach their end of life, we’d replace them with heat pumps. I think that these two systems are the largest sources of our current carbon emissions, based roughly on dollar expenditures. It doesn’t seem environmentally responsible to replace them early, just to feel “green”. Maybe I’m wrong.

We swapped out our gas cooktops for induction units. Faster cooking, cleaner surfaces, more controllable, and less indoor pollution.

In Massachusetts, we have an outdoor propane grill, but in Gainesville, we’ll have an outdoor electric grill, plugging into a normal 120 volt outlet. Once I’ve tried that for a while, maybe I’ll ditch my propane grill when the tank is empty.

Just say ‘no’ to av-gas?

Flying uses lots of fossil fuel. I’ve read that each flight we choose to make may dominate our annual carbon emissions, beyond cars and HVAC. But the trade-offs between flying vs. driving vs. public transit are complex, so I guess that most of the big emission must be from the long distance travel itself, not from the mode we use to get there.

This is the one area where we’ve actually restricted our lifestyle to reduce emissions. Until this month we haven’t flown for nearly five years. The pandemic was a factor, but mostly we’ve changed our plans and picked nearer vacation spots that we could drive to. Most of those trips were in the Forester and the math seems to work out that two people sharing a gasoline-powered car from say, Massachusetts to Florida, emit less carbon than two people flying there. But it’s a close thing because one person flying there appears to emit less than one person driving that car. So when I needed to do a site visit in Gainesville a few weeks ago, I flew down and back in one day. I feel ambivalent about that, but the things I accomplished couldn’t have been done remotely. Still, that one trip will probably dominate my carbon emissions this year. And it isn’t going to be the last flight of my life. I struggle with these trade-offs.

Cool gadgets

While researching systems for the house in Gainesville, I ran across some interesting equipment for reducing domestic energy use. I’ll start with my favorite one, even though we can’t use it in that house. (Darn!)

I love hot showers, but it bothers me that I’m using each gallon of hot water for only a few seconds and then the heat goes right down the drain. This is not about guilt; I’m an engineer and this seems like a lousy design. Can’t we recover half of that heat and reuse it? Yes! It’s called a drain water heat recovery system. These are cheap ($300 + installation) and they warm up the cold water supply going to your shower from the water going down the shower drain. Since the incoming “cold” water gets warmer, you need less “hot” water supply to get the temperature and flow you want. This device is only useful where a drain has a prolonged period of warm water flow while the “cold” supply is also flowing, i.e., in a shower. How cool! But the device needs about 3 feet of vertical space below the shower drain. If you have a basement, that might work (watch your head), but the house in Gainesville is on a slab like everybody in Florida. (The water table is only a few feet down.) So the exchanger would corrode in the ground below the slab and start leaking. Then out come the jackhammers punching through our shower floor to repair it. Alas, no. But maybe in your house, Gentle Reader.

We do get to use another type of heat exchanger: an air-to-air heat exchanger to control the air coming into and out of the house. As a byproduct of making houses well-insulated, new ones are nearly air-tight. The inside air would get stale and polluted if we did not explicitly supply fresh air and exhaust stale air. But the fresh air has to be heated or cooled to match the indoor temperature. Why not use the exhaust air to help do this? Hence the air-to-air heat exchanger. Not only does this transfer heat either way as needed, but the resin walls of the exchanger transmit moisture as well! Wow, that’s amazing! As a result, there’s no condensation in the unit and no need to drain condensate or lose energy to condensed moisture. The unit doesn’t consume much power and it can be programmed to run when desired.

Given all the rain in Florida, you’d probably be surprised to hear that they often have water shortages. (This isn’t a GHG emission issue, but while I’m on the subject of conservation decisions in Florida …) So I wondered if we could recover waste water and use it for something, say to water the landscape? Two problems. We prefer native plants, which don’t need extra watering. Duh. And slab construction doesn’t favor a holding tank and its plumbing. Maybe in Arizona. So the water goes to the sewer.

My other guilty plumbing pleasure is hot water at the sink for washing. In Sudbury, I have to run the hot tap for two minutes before the water gets hot. (Yes, I timed it.) I know, “first world problem”—except for the water shortage issue in Florida. That’s 3.2 gallons thrown away every time. There are two ways to tackle this. One is a point-of-use electric tankless heater. They’re inexpensive and they fit under each sink, but they require a heavy duty electric line and their own circuit breaker. And they use much more power to heat the water than a heat pump hot water tank does. Bummer.

Our plumber suggested a different approach, recirculating hot water. Instead of running 3.2 gallons down the drain while waiting two minutes, the hot water line under the sink preemptively recirculates back into the cold water line through a small pump under thermostatic control. It’s quite cheap, easy to retrofit in existing construction, and one can program it to recirculate at specific times of the day, like when we wake up and before meals. At first I begrudged the idea of having hot water loops running throughout the walls while running an air conditioner to cool the house. Seems stupid. But the timer function means that those loops would only get hot at times when we were likely to call for hot water anyway, so even without the recirculating pump the hot pipe would get hot at that time. So the extra waste heat would be small. And all the water would be saved.

The bleeding edge

Any attempts to personally reduce our GHG emissions are fraught with uncertainties, and all emerging technologies have questionable reliability and value. I touch on a number of them below.

Embodied carbon?

Surely the greenhouse gases emitted by making a Tesla from scratch are different from those emitted by making a plug-in hybrid RAV-4. But which way and how much? Does one break even at some point? Studies argue about all of this for just about anything you might ever buy. A lot of most people’s carbon footprint is in their purchases. Each new study tries to account for more factors more carefully. This is another way we consumers can go wrong or just give up. Definitive knowledge often doesn’t exist yet. And usually, even our intentions aren’t pure.

For example, when we switched from gas to induction cooktops, it was due to a preference for induction cooking, not because our gas cooktops needed replacement. Beforehand, we bought a portable induction cooktop to try out the experience and we fell in love. Try wok cooking on induction and you’ll be totally spoiled. And water boils super-fast with no wasted heat. So, to be honest, the embodied carbon in our newly purchased induction cooktops was totally optional and premature, not part of an end-of-life replacement. At the time, the issue of indoor pollution from gas stoves was just emerging and it reinforced the decision we’d already made. My point is that our motives were a mixture of “green” and “greed”.

On that theme, it’s a much bigger source of embodied carbon to build a new house at all. Is choosing various energy-efficient components for such a project really just arranging deck chairs on the Titanic? I hope not. The house will be around for a long time, so it should pay back investments in efficiency.

Carbon offsets?

When you fly or rent a car, you can often purchase “carbon offsets” which attempt to fund programs that compensate for your trip emissions by taking carbon out of the atmosphere somewhere else. I mentioned above that RECs are likely to be ineffective and I am similarly skeptical of carbon offsets at present. But it’s important to understand that these fields are advancing quickly. When valid criticisms are discovered, dedicated people get to work improving these systems on a large scale. So maybe carbon offsets will become a reliable contribution in the near future.

Integrated heat transport?

Environmentally speaking, my biggest frustration about building a house, or living in a house, is that the systems that move heat around don’t work together. Consider the new house in Gainesville as an example. There will be five systems that move heat: HVAC, domestic hot water, refrigerator, fresh air supply, and pool heating. All of them are separate systems and they rely on ambient air to source or dump heat (often at the same time!) Not using the ground, mind you, which is at a “rock-solid” 70 degrees Fahrenheit year round. Let’s contrast that with a Tesla vehicle, which has a central heat transport manifold that has 14 different modes of operation. It has a coolant system and a refrigerant system linked by two heat exchangers about the size of your fist. It can cool or heat anything in the car. Why can’t I heat my domestic hot water by cooling my refrigerator? Why can’t I cool the air in my house by heating my pool? Why can’t I heat my house from stored very hot water that I heated up at an earlier time of day when electricity was cheaper? The answer of course is “legacy”. These systems evolved separately. But if we want to get serious about energy efficiency, these systems will have to work together in a “plug and play” fashion. And big loud fans that pump heat and cooling into the atmosphere will have to be replaced by quiet little water pumps that link to the stable ground. Not only do I want this in my house, I’m ready to invest in companies that pursue the idea. Not because I’m “green”, but from “greed”. It’s a better idea and it should grow and make money.

Carbon removal as charity?

I would like to help fund GHG absorption programs as a form of charitable contribution and to personally reach the equivalent of net-zero emission, and even go beyond, to net-negative emission. But it just doesn’t seem like the bugs are worked out of this part of the system yet. A lot of it seems to be wishful thinking. I continue to research this intensively because it seems to be the only way to personally stop being part of the problem some day.

Summary & conclusion

My journey convinces me that the average citizen has a number of opportunities to reduce their carbon emissions. The easiest one is to find out if you can sign up for 100% renewable electricity, usually in a group plan. If your municipality doesn’t offer such a plan, look into plans from organizations such as Audubon, Sierra Club, Nature Conservancy, etc. The second opportunity is to replace your aging energy systems with non-fossil-fuel using systems, such as heat pumps and EV’s or plug-in hybrid vehicles. The more you switch to systems that use electrical energy, the more you can take advantage of renewable electricity when it becomes available to you. The third opportunity is to invest in solar and/or wind power generation on your property. This is a thriving growth sector with a lot of government incentives to help get over the hump of the initial expense and start drawing on the long-term payback. The bottom line is, there’s almost bound to be steps you can take.

Narratives are supposed to wind up in confident triumph, but this one doesn’t. Our road goes onward in the fog, with lots of challenges ahead. Our species is facing a horrendous mess and frankly, we’re floundering. Denial, short-term greed, and paralysis are widespread. But so too are determination, compassion, and ingenuity. Researching this post, I found that many other people are building a better future for us every day. Don’t be cynical, don’t be selfish, and don’t be hopeless. Thousands of generations of our descendants will depend on us to do the right things now. Let’s not fail them.