I doubt you have heard of the “replication crisis”, Gentle Reader, which is odd, because it is certainly one of the most important issues in science in the last several decades. It may sound obscure at first, but in terms of its wide and relevant impact, it’s right up there with climate predictions and AI. But unlike those issues, the replication crisis receives only sparse publicity. Why? It’s tempting to think that the subject may be so embarrassing to scientists that they would rather clean up the mess quietly. But a more plausible explanation is that this is a complex, systemic problem that evolves slowly, so it doesn’t package well as “news”. I’m writing to you about it because I think everyone should know enough about this issue to be informed consumers of science news.

TLDR: Scientists have established that about 2/3 of their newly published findings fail to be reproducible, meaning that, despite all of their diligence, most of their new “discoveries” are actually false. Therefore, a rational consumer of science news should be doubtful of the majority of what they read or watch. The scientific community is working on fixing this huge problem, but it’s going to take many years.

This sounds pretty scary, doesn’t it? Is it even true? Perhaps I have gone off my meds and have become a raving science-denier? Your skepticism is wise. As Carl Sagan put it, “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence”. So I’m going to provide you with a good deal of evidence here. I’m hoping to provide enough to be convincing, but not so much as to be tedious.

Although I’ve been studying this topic for a decade, I begin this post with a good deal of trepidation. The subject is a sprawling mess, with many participants pointing their fingers in all different directions. Calling it a “can of worms” doesn’t even do it justice. After encountering more and more, and yet more, of this problem, I’d call it a “55 gallon drum full of worms and other squirming nasties”. So why devote writing space and reading time to something so extensively unpleasant? Despite the current mess, science is the best thing that has ever happened to the human species. Our lives, and the lives of everyone we know are longer and better in many ways because of the unstoppable juggernaut of true understanding that is science. I’m confident that the culture of scientific truth-seeking will, in time, triumph over this huge mess of worms. In the mean time, we mustn’t turn away. So let’s get started.

Most new science is false

If you were to encounter a news item saying that scientists had just determined that eating rutabagas reduced your cancer risk by 30%, would you start chowing down on rutabagas? Order them in bulk from Amazon? Or would you confidently ignore the claim and await a reversal of it by a subsequent study? I would wait. Nutrition science has reversed itself in the news so many times that we pretty much ignore what we don’t want to hear from them. They are not quite a laughingstock, but they are certainly the poster child for the replication crisis. I read somewhere that nutrition scientists have fretted among themselves at conferences about whether their field can even get continued funding. I don’t know if that’s true, but I think they should be worried.

The problem of low repeatability in published science has been lurking in the shadows for an unknown length of time, but it burst into the open in 2005, when a Stanford epidemiologist named John Ioannidis published an essay titled, “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False“. (A very accessible summary is here on Wikipedia.) That claim is pretty bold and blunt, and it got the attention of a lot of scientists.

The first question on everyone’s mind was, “is his claim true or false?” Rather than argue, many scientists set out to study whether Ioannidis’ assertion was correct. Each chose a collection of published results of interest in their field and coordinated teams to repeat those experiments to see whether their new results confirmed the original findings, or not. These are called replication tests. Unfortunately, over and over, these researchers found that Ioannidis was indeed right. The majority of replication tests failed to find the original effects and those that did so usually found weaker effects. To be specific, here is a table drawn from the excellent Wikipedia article on the replication crisis. (Essentially the same data can be found in Aubrey Clayton’s recommended book, “Bernoulli’s Fallacy: Statistical Illogic and the Crisis of Modern Science“.)

Field Estimated replication success rate

Medicine 20/34 (59%)

Psychology 35/97 (36%)

Social science 13/21 (62%)

Preclinical cancer studies 6/53 (11%)

Economics 11/18 (61%)

Preclinical pharmacology studies < 50% (n > 100)

The weighted average success rate across all 323+ replication tests summarized here was about 38%. The sample sizes are too small to say whether the different fields actually have different rates or not, but the total average is probably pretty accurate.

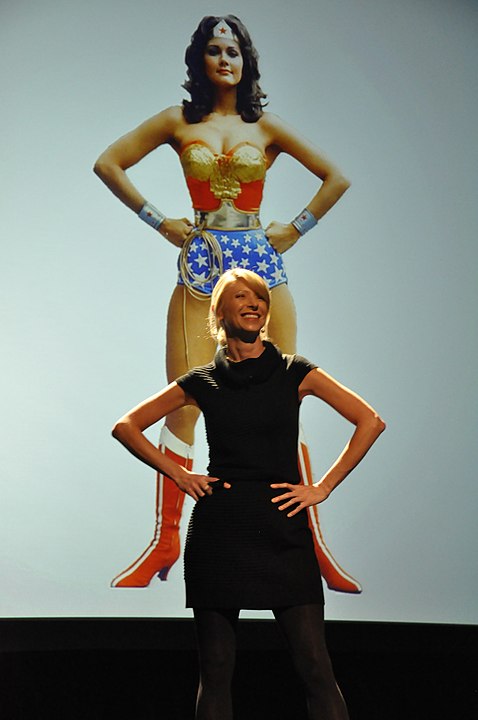

These were not backwater findings that were tested, and many of them had been published in top journals, such as Nature and Science. You’ve probably heard of some of the “discoveries” that didn’t stand up under this scrutiny. For example power posing failed: the idea that adopting a powerful posture increases self-confidence. It’s a fun idea and I’ve tried it myself, but it doesn’t replicate under repeated testing.

In fact, one whole sub-field of psychology called behavioral priming was largely undermined, to the point where, in 2022, Daniel Kahneman (Economics Nobel Prize 2002) said, “behavioral priming research is effectively dead“, because grad students won’t touch it. Priming is the notion that our behavior can be influenced by prior stimuli that bias us without our conscious awareness. You may have heard of the 1996 study that popularized the field; it concluded that test subjects exposed to words related to old age walked more slowly when leaving the test. Among many other results in priming, this finding did not replicate. At this point, it is not clear that “priming” ever really happens.

It’s fair to say that most scientists (and others) were surprised that the replication rates in all these fields were so low. Oh, there were a very few voices who haughtily said, “I knew that, didn’t you?” and a few who said, “it’s cutting edge stuff, what did you expect?”, but most scientists were probably chagrined, and thinking, “so why am I reading all these articles? And worse, why am I writing them?” And their sponsoring organizations may have thought, “why are we funding this stuff?” That’s when it started to be called a crisis. But before I continue the story, I need to provide some basic foundation for you.

Why is replication important?

The goal of science is to find ways of predicting what will happen by developing rules about causes and effects. Nobody really cares about how you spent your summer vacation in a room full of mice unless you learned something about mice that can be repeated by others (and hopefully it can then be applied to humans, not just mice). So, no matter how much brilliant work you did, no matter how careful you were, no matter how exciting your theory is, if your result can’t be replicated by others, then it isn’t useful for predictions and it belongs in the dustbin. Successful replication is the essential test of science.

[Digression: replication tests aren’t easy to do correctly, even in “hard” sciences such as physics. In junior lab at MIT, my partner and I could not get the canonical double hump to emerge from our replication of the legendary Stern-Gerlach experiment. (The two humps indicate that electrons have intrinsic quantized magnetic fields, “up” or “down”, which is just pretty unbelievable until you see it happen.) Instead of thinking that physics was broken, our Professor Kleppner proposed a particular flaw inside our detector. The head lab technician, “Angelo”, tore down the vacuum apparatus overnight and had it working correctly the next day. Professor Kleppner had been exactly right and we saw the famous double hump. Junior lab was supposed to teach us basic competence with physics lab equipment, but what I learned was, “professors talk with gods, but lab techs are gods.” The consensus among us students was that lab competence was measured in “milli-Angelos”, meaning that most people had only a few percent of his skill.]

To bring the focus back to the post-2005 replication programs, I was relieved to learn that most of those tests were performed with the willing assistance of the original research teams, so that naive errors could be avoided and the tests would have a fair chance of showing the original effects again, if they were real. No one was more shocked than the original teams when new data often showed little trace of the effects they had published.

Why wasn’t this problem seen before it got huge?

Despite the importance of replication tests, almost none were published before Ioannidis came out and claimed that the emperor of science was very scantily clad. The reason was simple: before then, you couldn’t get grant money to repeat somebody else’s work. If we all assume that most research findings are true, then we won’t pay to check them. Also, although many individual scientists had failed at some point to replicate a colleague’s experiment, there was no market to publish such results. And if it’s not published, nobody knows how widespread it is. After Ioannidis’ essay, the question was suddenly of great interest and you could get funding for replication testing and you could find a publisher. So the problem of low reproducibility had snuck up on everyone because they had assumed that current methods had to yield “mostly true” results. Oops!

There was one area of exception where replication testing had been done extensively all along, but it was not done publicly. Pharmaceutical companies thoroughly monitor basic published research and they often start their drug development process by attempting to repeat promising published experiments. Each company was well aware of their own very low success rate at replication, but they don’t publish their internal findings, in order not to assist their competitors. Once the replication problem broke into the open though, Amgen and Bayer each released collective studies showing that their in-house replication testing had a 10-20% success rate. One researcher at another pharmaceutical company told me in 2024 that 10% was still their internal rule of thumb.

So the reality and severity of the problem was known in local pockets, but it wasn’t part of the collective consciousness in science before 2005. As far as I can tell from Ioannidis’ references in his essay, he personally connected the dots in his own field of epidemiology and publicly extrapolated to other sciences. His provocative essay galvanized attention to the issue on a large scale.

So what?

Other than disappointment, and maybe embarrassment, does it really matter if most published research findings are false? After all, it is the cutting edge. Should we just accept that caveat and move on? Most players in science have answered, “no, this isn’t okay.” More specifically, the producers, funders, and consumers of new science all have different reasons for their being unwilling to accept this status quo.

Having read many dense scientific papers, and having written a few, it is obvious to me how much labor and hard thinking they represent by those who produce them. The thought of peer review and the scrutiny by many smart readers in your community makes you try your very best not to mess up anywhere. Journal editors have similar incentives as well. Research publication is a high-wire act. If you fall, you fall in public. So, to be convincingly shown that the basic odds will be against your findings being correct is a heavy personal challenge. I think most scientists react to that news by wanting to know how they can improve their own productivity. They simply don’t want their work to be wasted time and they don’t want to be wrong in public. Unless one is in denial, it’s a powerful incentive to improve.

Those who fund science are constantly offered more alternative projects than they can possibly finance, so they seek to maximize the effectiveness of their spending choices. If the majority of money is being wasted now on generating false results, funders are ready to insist on changes that may improve their hit rate.

But the productivity concerns of the producers and funders of science are dwarfed by the suffering of those awaiting new life-saving knowledge at the cutting edge of research. Consider for example the low replication rate found in a sample of preclinical cancer studies: 6 out of 53. The other 47 misleading initial findings represented blind alleys and false hopes for those who may have had no other hope. The same heartbreaking burden applies in any field where new science has the potential to alleviate our suffering, most obviously in medicine, pharmaceuticals, and economics. False findings keep wasting time, money, and lives until they are discovered to be false.

In a wider sense, society as a whole is a consumer of scientific knowledge. The track record of science in improving our lives has given scientists a special level of respect in our society. But with politically and religiously motivated denial of proven scientific truths growing in the public mind like metastatic malignancies, this is a particularly bad time for science to have a genuine crisis of credibility. The sooner scientists can turn this around, the better.

So this is not a crisis of embarrassment and inefficiency; it’s a crisis of suffering and death, and possibly a crisis to the Enlightenment itself. But take heart, Gentle Reader. Science as a concept, as a practice, and as a culture is not so frail an enterprise as to be done in by this discovery, nor are scientists powerless to reverse this painful setback. Science can analyze and solve this problem, too. In my next post on this subject, I’ll write about the systemic factors that cause this sad state of affairs, and then about current efforts to cure the malady. Stay tuned.